Columnists: Erica Hope and Brook Riley,

Published on: 20 Jul 2012

What gut feelings did to the EU Energy Efficiency Directive

Two days before negotiations on the Energy Efficiency Directive were concluded in the night of 13/14 June, Martin Lidegaard, the Danish Climate and Energy minister, told us how baffled he was by the Council position. Why did Member States support the benefits of meeting the EU's 20% by 2020 energy savings target, but insist on a Directive which will only deliver 15%?

We think an answer might lie in work compiled by Dan Gardner - an award winning Canadian journalist and author - on conflicting systems of thought. He puts it down to a conflict between ‘head’ versus 'gut' (or reason versus instinct). The first is ‘calculating, slow and rational’. The second ‘intuitive, quick and emotional'. Gardner’s work does much to explain the muddled thinking on the Directive.

Let's start with the ‘head’ arguments. Reducing energy demand is the obvious solution to the EU’s growing dependence on oil, gas and coal imports. At the same time, because CO 2 emitting fossil fuels dominate the EU’s energy mix, saving energy is crucial if we are to address global warming.

Then there’s money: the net benefits of meeting the EU’s 20% by 2020 energy savings target are likely to exceed €200 billion per year, according to work from Ecofys, a research group. This is a huge number: equivalent to over a third of the total budget deficit of the 27 Member States in 2011.

But many policymakers in the Member States instinctively took a very different view of the Energy Efficiency Directive. They had three main gut feelings.

The first - reinforced by the short-termism arising from the Eurozone crisis - was that GDP growth is dependent on increasing energy consumption. Saving energy, in other words, was seen as rationing, and entailing recession.

The second gut feeling was that it costs money to save money. Governments might ultimately benefit, but only with sufficient upfront investment which they felt obliged but unable to provide.

The third was that markets alone would suffice. If energy savings make such good financial sense, surely businesses would be on the case, whether or not there was a Directive?

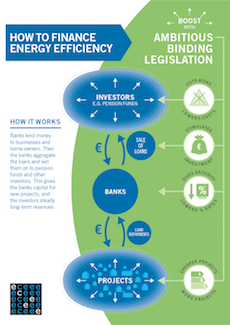

Frustratingly, information and studies which showed the reality was more complex fell on deaf ears. Commission research showing that meeting the 20% target would accelerate GDP growth gained little attention. Nor did warnings from private investors that they would finance energy savings - but only with tougher EU legislation to provide investment security (i.e. the binding targets model used for the EU’s climate and renewable energy targets).

The fact that businesses gain a competitive edge by using less energy to produce more efficient goods also went unheeded. And as for the markets, it was their failure to act that, more than anything, made the Directive necessary.

It's fear, of course: fear of change. Instinctively, most policymakers stuck to what they knew (no restrictions on energy usage). And those Member States who preferred a watered-down Directive - which is to say almost all - felt reassured by lobbying from influential heavy industry and energy companies with a vested interest in keeping energy consumption high. Counter arguments were ignored. Even though good economic and environmental sense supported the case for making the Directive as strong as possible, for the Council, at least, ‘gut’ beat ‘head’.

Gardner calls this confirmation bias. ‘Once a belief is in place’, he writes, ‘we screen what we see and hear in a biased way that ensures our ‘beliefs’ are proven correct’. In all likelihood, key decision makers in the Member States genuinely failed to realise that energy savings are a solution to many of their financial and environmental difficulties. They were simply not tuned in to the benefits.

There is no easy solution. In the end, it’s all down to critical mass and confidence that saving energy is a plan that adds up.

Consider the 2009 Renewable Energy Directive: by any measure, a more ambitious piece of legislation. There are many explanations for this, but undoubtedly in renewables’ favour when the law was being negotiated was the close understanding and working relationship between a critical majority of governments, businesses, investors, and civil society organisations. Differences were technical (which type of renewable energy?) rather than conceptual (why renewables?). Everyone understood the benefits.

This is the approach needed to strengthen EU legislation on energy savings: coalition work, smart communications, and a very clear awareness of what consumers and businesses stand to gain. If we can get it right, ‘head’ and ‘gut’ should be more in tune for the implementation of the Efficiency Directive in 2013 (Member States can exceed the EU requirements, if they so choose). And because we all tend to believe what we see, the fact that there will be additional savings compared to existing legislation should pave the way for an ambitious review of the Directive in 2014. Sound reasonable?

Other columns by Erica Hope and Brook Riley

Mar 2013

Feb 2013

Jul 2012

Mar 2012

Mar 2012