Columnists: Erica Hope and Brook Riley,

Published on: 23 Mar 2013

It's the economy, stupid

The 27 EU Commissioners met to discuss 2030 climate and energy policies in February. The background papers for their meeting were leaked – and as you can imagine, repeatedly perused. You can see them here . We keep coming back to this extract, which we think goes to the heart of the Commission’s thinking:

‘This 2030 framework must be sufficiently ambitious to ensure that the EU is on track to meet longer term climate objectives, but it must also reflect the consequences of the on-going economic crisis, the budgetary problems of Member States who have difficulty to mobilise funds to deliver the 2020 targets and the concerns of households and business about the affordability of energy.’

When we read this we’re struck by the Commission’s take on climate action. The paper presents it as something that needs to be done despite its (supposedly) negative impact on the economy. There’s no space for the argument that climate action – and energy savings in particular – will help resolve the economic crisis, cut energy costs, create jobs etc.

This ‘old-think’ problem isn’t new of course. It was precisely because we wanted to counter it that, back in 2012, we asked research group ECOFYS to look into the financial benefits of tough energy savings legislation for 2030. Their results are now in: they estimate the net benefits at about €250 billion per year, or the same as Denmark’s GDP.

This is persuasive stuff. But the Commission’s paper is a reminder that we must stay focused on winning the argument that the benefits outweigh the costs. The perceived economic and competitiveness impacts of climate action are the issue which will overshadow the whole 2030 debate and determine how ambitious national governments – the real players in this game – are prepared to be. For this reason, we must make sure governments and citizens understand that energy prices will inevitably increase in coming years as Europe’s increasingly rickety energy infrastructure is replaced. But with the right choices – using less energy and switching to renewables – total energy costs will decrease.

Having said that, simply arguing the economic benefits of energy savings, greenhouse gas cuts and renewable energies is not enough. We also have to show how they will be delivered. Here’s an extract from notes of a meeting we had with Danish government representatives:

‘They [the Danes] firmly believe green growth is a way out of the economic crisis. They have repeatedly tried to convince other member states of this – for example during the negotiations on the energy efficiency directive. But in many cases member states do not have green businesses, and they simply don’t know how to ‘green’ their economies. Therefore they dig their heels in and resist. Despite the obvious fact that while there are risks that the green economy might not take off, the risks of not supporting it are far greater.’

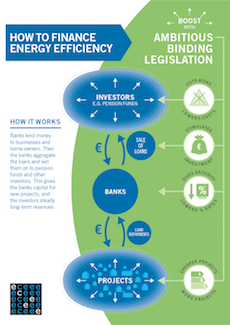

We think this is why binding targets are so essential. As long as there is no obligation to deliver energy savings, why bother to invest any effort or creativity in the problem? Without necessity, good ideas are gathering dust. The energy service company model, for example – where investors finance energy efficiency improvements for consumers and businesses, then recoup their costs through energy bills – could be a truly transformative concept. But it remains a marginal one. This is just one of the things binding energy savings targets for 2020 and 2030 could help to change.

Other columns by Erica Hope and Brook Riley

Mar 2013

Feb 2013

Jul 2012

Mar 2012

Mar 2012