Columnists: Walt Patterson,

Published on: 14 Oct 2010

Managing energy wrong

We are managing energy wrong. We say 'energy' when we really mean oil; or coal; or natural gas; or electricity. They are not the same, not interchangeable. But calling them all 'energy' makes too many people, especially politicians, think they are the same - that one can substitute for another. We talk about 'energy supply', when we really mean 'oil supply' - not the same as 'gas supply' or 'electricity supply'.

Why do we need these supplies? That is the key detail we so often ignore. We need fuels and electricity to run stuff. What matters is the stuff - lamps, motors, electronics, appliances, industrial plant, vehicles and especially buildings. This stuff, this technology, provides what we want - comfort, illumination, motive power, refrigeration, mobility, information and communication. The technology is what matters. Oil by itself is almost useless. Natural gas by itself is downright dangerous. Electricity as we use it does not even exist by itself. It's a process in technology. Fuels are only useful because of technology.

What we call 'energy policy' today still concentrates on fuels and electricity - what we used to call 'fuel and power policy'. It takes user-technology for granted and ignores it, except as aggregates and averages of so-called 'energy demand'. But we do not have 'energy demand', or an 'energy problem'. We have many different, specific and distinct problems: how best to provide many different energy services all over the world, with many different specific user-technologies, that may - or may not - require specific fuel or electricity.

Energy policy today takes as its central premise the role of competition, to ensure optimum service to users. We presume that the key competition is between different suppliers of a particular fuel or electricity, and that the aim is to make the price of a unit of, say, gas or electricity as low as possible. Most users, however, have no idea of the unit price of their gas or electricity. What matters to them is the bill. What they want is a low bill. Low prices may not lead to low bills - on the contrary.

That is because the real competition, the competition that really matters, is between fuel and technology. Better user-technology requires less fuel to deliver the same or better services. Fuel and user-technology compete directly with each other.

Key competitors for ExxonMobil are not Shell nor BP but Toyota and Honda. Competitors for Gazprom are Europe's manufacturers and installers of thermal insulation. Competitors for EdF and E.On are the manufacturers of compact fluorescent and LED lamps; and so on. We should foster this crucial competition between user-technology and fuel, to upgrade our user-tech and infrastructure, as the direct objective of coherent strategy for climate and security.

We can start by stating explicitly what we know to be true but have been too mealy-mouthed to say. We talk about a low-carbon future in a low-carbon world. Let's not be coy. Low carbon means low fuel. We need to use less fuel. We've known how for decades. We have to invoke better technology - better buildings, better lamps and motors and electronics, better vehicles, and so on.

But governments and regulators need to change the rules. At the moment, the large international corporations that call themselves energy companies make their money by selling fuels and electricity. But real energy policy will no longer focus on such short-term batch transactions. It will focus on investment in energy performance. If governments and regulators change the rules, energy companies will change their business plans, to make money by upgrading our user-technology and infrastructure.

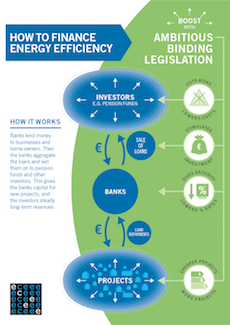

We want, for instance, to encourage electricity and gas suppliers to invest in upgrading the premises of their customers - to make money while selling less fuel or electricity. When the supplier invests in a customer's premises, by installing insulation, better lighting, better doors or windows, better controls, microgeneration or some other performance upgrade, the supplier receives a return on the investment by a suitable surcharge on the bill. But the upgrade reduces the amount of fuel or electricity used, making the overall bill not higher but probably lower.

The key is to tie the requisite contract not to the property-owner but to the property itself, a relationship akin to those for incoming supply-pipes and wires. If a particular owner changes supplier, or even sells the property to a different owner, the contracted payments to the original investor continue.

Energy policy and regulation are not just about oil, gas, coal and electricity, but about technology and infrastructure. Imaginative innovations and opportunities abound. Governments and regulators should show us the way.

Other columns by Walt Patterson

Oct 2010