Columnists: Andrew Warren, British Energy Efficiency Federation

Published on: 14 Feb 2017

If the UK is leaving the EU, can it really work to weaken EU energy efficiency rules?

Does Brexit really mean Brexit? If so, it isn’t deterring two UK government Departments from deliberately seeking to water down the proposed strengthening of two European directives. Both are officially designed to promote “ the most cost-effective ways to support transition to a low carbon economy.”

Last December the European Commission published a new thousand-page strategy, intended to deliver “A Clean Energy Package for Europeans”. Launching it, Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete began by deliberately insisting: ”Let me start with energy efficiency first.”

Although six of the eight dossiers in the package cover energy production, Cañete’s declared “priority” has been taken up by the European Council, representing national governments. Malta, which assumed the Council of Ministers’ six month presidency last month, is fast-tracking the Commission’s proposals to toughen two existing directives concerning energy saving.

These are the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), and the Energy Efficiency Directive. It will also expedite priorities on the eco-design of energy using products, both reviewing existing standards and introducing new products within the A to G measurements.

Cañete emphasises: “I am particularly proud that we are proposing a binding 30% energy efficiency target for 2030, up from the current indicative target of at least 27%”.

It is this declaration that, more than anything else, seems to be incurring the ire of the departing Brits. Three years ago, the Cameron Government fought a strong rearguard action to block both any energy saving target higher than a 27% improvement (from a 2005 baseline), and to ensure that it was neither legally binding nor required any firm action from individual governments.

Consequently the European Commission has been monitoring the absence of progress. It already estimates that “current national and EU energy efficiency frameworks will lead to a reduction of approximately 23% in primary energy consumption by 2030” – a very substantial shortfall even on that modest 27% target.

Many other governments – including Germany, Denmark and France – have always sought a more ambitious and legally enforceable target, including designated national contributions towards the total. Whilst the UK Government has formally told the House Commons EU Scrutiny Committee that it intends to be “fully involved” with negotiations, those in the other 27 member countries are confident that – once having begun the Brexit process this March – its ability to influence others to follow its more timid approach will be very limited.

Meanwhile, the European Parliament had voted to instruct the Commission to examine the likely impact of a 40% reduction target between 1995 and 2030. Significantly the EC’s formal impact assessment has demonstrated clearly that in terms of making an impact. a 40% reduction target would be significantly more effective.

The Brussels-based Coalition for Energy Savings said: “Every additional 1% of energy savings matters. Each could be taking 7 million people out of fuel poverty, securing 500,000 local jobs, avoiding 37 million tons of CO2, and cutting EU gas imports by 2.6%,” Even so, Cañete is limiting his objective to the more modest 30% figure.

The UK’s EU scrutiny committee, (chaired by the veteran anti-European Conservative MP Bill Cash) is nonetheless apoplectic. It is thundering that “the nature of these targets will have a substantive impact on the UK” and that (inevitably) “the Commission may have underestimated the costs to business of the proposed changes”.

But perhaps recognising the weakness of the UK’s position, the committee adds “we would also welcome any early indication as to whether the Government’s concerns might be shared by others”.

The reason why these new texts are pertinent to the UK is that, on the present timetable, they are scheduled to be agreed by the end of 2017. Indeed the Maltese Presidency currently intends to gain agreement within the council of energy ministers meeting in Valetta due on June 26. Even if that proves too optimistic, so long as full agreement is achieved at least 12 months before Brexit becomes a reality – probably April 2019 – it will be the contents of the new directives that will be transferred over into UK law.

Prime Minister Theresa May has announced that it will then be up to her Government to decide which parts of which of the transferred “acquis” – the portfolio word for all European requirements - will be retained.

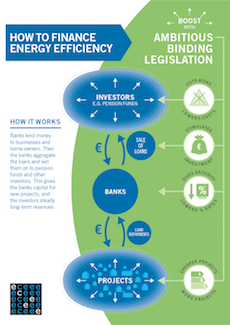

The European Commission has concluded that “The cheapest energy, the cleanest energy, the most secure energy is the energy that is not used at all. Energy efficiency needs to be considered as a source of energy in its own right. “It is one of the most cost effective ways to support the transition to a low carbon economy and to create growth, employment and investment opportunities”.

The United Kingdom has unilaterally decided to divorce its future from the rest of Europe – both EU and European Economic Area. Nobody outside the UK is forcing it to do so.

Last week’s Brexit White Paper is unequivocal:

The government is committed to ensuring we become the first generation to leave the environment in a better state than we found it. We will use the Great Repeal Bill to bring the current framework of environmental regulation into UK and devolved law. The UK's climate action will continue to be underpinned by our climate targets as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008 and through our system of five-yearly carbon budgets, which in turn support our international work to drive climate ambition.

Seeking so overtly to reduce the ambition of the remaining 27 Member States to ensure that such cost-effective options are legally adopted, would directly transgress that commitment. The UK should have the modesty to adopt just a modest “watching brief” during these negotiations.

***************

Fact box:

Many of the other proposed changes to the two directives, whilst important, are fairly technical. Within the European Performance of Buildings Directive, these include:

- the introduction of a smartness indicator rating the readiness of a building to adapt both to the needs of the occupant and the grid.

- requirements for electro-mobility infrastructure, including provision of charging points at developments

- offering building automation and energy monitoring systems as an alternative to inspection

- incorporation of fuel poverty considerations

- an open database of Energy Performance Certificates, to track actual consumption, particularly if publicly funded

- incorporation of an energy as well as carbon saving metric within EPCs, building regulations etc.

Lead UK Department: Communities & Local Government

Within the Energy Efficiency Directive, some of the other proposed changes are:

- The extension of existing annual energy savings obligations for Member States lasting well beyond 2020

- Criteria to be altered regarding how and which savings should be counted by governments under existing Article 7

- Access increase for consumers to consumption information

Lead UK Department: Business Energy and Industrial Strategy

Other columns by Andrew Warren

Dec 2009